When a residential building is complete, the features most visible to occupants and visitors are finishes: walls, floors, ceilings, windows, and fixtures. These surfaces shape how a home appears, but they do not define how it functions.

But a different set of invisible energy features is central to residential performance. These elements are structural, layered within assemblies, and concealed once construction is complete. They are not designed to be visible. They are designed to separate the indoor environment from the outdoors and to regulate the movement of heat, air, and moisture across that boundary.

Understanding how a home functions therefore requires understanding systems that cannot be evaluated visually after construction.

The Building Envelope: The Functional Boundary That Controls Energy Performance

The Building envelope is the part of a building that separates the controlled indoor environment from the uncontrolled outdoor environment; according to the U.S. Department of Energy’s building envelope definition, it includes walls, windows, roof, and foundation as the primary barrier between interior and exterior spaces.

This definition establishes the envelope as a functional boundary, not a decorative one. Its purpose is not appearance but separation. Once a home is finished, nearly all components of this boundary are concealed. Wall cavities contain insulation. Air barriers are layered behind finishes. Roof and floor assemblies include materials intended to resist heat flow and air movement. Because the envelope exists within the structure, it cannot be evaluated through surface inspection alone. Its presence is assumed based on design, installation, and verification rather than observation.

Exterior and Interior Forces Acting on the Building Envelope

Several forces act simultaneously on residential structures. They originate both outside and inside the building and include temperature differences, air pressure differences, moisture in multiple forms, wind, and mechanical system operation.

Exterior environmental forces include temperature variation, air movement, humidity, rain, snow, and light exposure. Interior forces include conditioned air temperature, humidity, occupant activities, and mechanical system pressures. The envelope must resist and manage these forces continuously across all assemblies.

The envelope is therefore not a single component but a system of layers and invisible energy features designed to respond to changing conditions. These layers must remain continuous across transitions, penetrations, and interfaces to perform as intended.

Heat Flow and Insulation: The Core of Energy-Efficient Home Design

Heat flow is one of the primary forces acting on the building envelope. Heat flow control is a fundamental function of envelope design. Insulation is identified as the primary element resisting conductive heat flow within assemblies. Insulation is typically placed within walls, floors, and ceilings or installed as continuous layers within assemblies. Once installed and covered by finishes, insulation is not visible.

Its continuity and placement relative to other control layers are determined during construction, not after completion. Insulation must be continuous and that gaps or interruptions reduce its effectiveness. These interruptions often occur at framing members, transitions between assemblies, and structural penetrations, locations that are not visible once finishes are installed.

Air Leakage and Air Sealing Within the Building Envelope

Air flow across the building envelope is driven by pressure differences. These pressure differences arise from wind, stack effect, and mechanical system operation. Air leakage occurs when air moves through unintended openings or pathways within the envelope. Training materials identify air leakage as significant because moving air carries heat and moisture. Leakage pathways are often located at joints between assemblies, penetrations for wiring and plumbing, soffits, decks, and interfaces around windows and doors.

Air leakage is not limited to large openings. It can occur through diffuse pathways across materials or through complex, indirect routes within assemblies. These pathways are hidden within the structure and cannot be observed visually once construction is complete. To address air leakage, air barrier systems are installed to provide a continuous barrier to air movement across the building envelope. Air barriers may consist of membranes, sheathing, or other materials designed and detailed to connect across assemblies.

Moisture Movement and Vapor Control in Residential Buildings

Moisture exists in multiple forms within and around residential buildings, including liquid water, solid ice or snow, and water vapor. Envelope design documentation identifies vapor diffusion as the movement of water vapor through materials, independent of air movement.

Vapor diffusion is driven by differences in vapor pressure and temperature. If not accounted for in design, vapor movement can result in condensation within assemblies. To manage vapor diffusion, materials with specific vapor permeance characteristics are selected and placed strategically within wall, roof, and floor systems.

Vapor control layers are not typically visible after construction. Their effectiveness depends on their placement relative to insulation and air barriers and on maintaining appropriate conditions within assemblies. As with other envelope components, vapor control performance cannot be evaluated visually after finishes are installed.

Rain Penetration and Water Management

Rain penetration is a critical consideration, particularly in climates subject to wind-driven rain. Rain penetration is driven by gravity, air pressure differences, capillary action, and momentum. To manage rain, wall systems are designed using strategies such as deflection, drainage, drying, and durability.

Drainage cavity wall systems include cladding, a drainage space, a water-resistive barrier, insulation, and interior finishes. These invisible home features rely on internal layers to manage water that enters the cladding system. The drainage paths and moisture control elements are concealed behind exterior finishes. Their presence and continuity cannot be confirmed through visual inspection after construction.

Layered Wall Systems and Concealed Performance

There are different wall system types, including drainage cavity walls and barrier walls. Drainage cavity systems incorporate multiple layers that manage air, moisture, and heat, while barrier systems are other invisible home features that rely more heavily on exterior surfaces. Layered systems are more effective at controlling heat, air, and moisture transfer.

In all cases, the performance-related components of the wall assembly are located within the enclosure rather than on its surface. This approach reflects an expectation that performance will be achieved through concealed invisible home features rather than visible features. Exterior appearance does not indicate how these systems are configured or installed.

Continuity Across Assemblies and Transitions

Envelope performance depends on continuity across walls, roofs, floors, and foundation assemblies. Training materials illustrate that failures often occur at transitions rather than within large uninterrupted surfaces. Common problem areas include roof-to-wall interfaces, soffits, decks, window installations, and penetrations for services. These locations require careful detailing to maintain continuous control layers.

Once construction is complete, these invisible home features are hidden behind finishes. Their performance cannot be evaluated without invasive inspection. As a result, envelope continuity is established during construction and verified through inspection and testing rather than observation.

How Invisible Energy Features Are Verified Through Inspection and Testing

Envelope performance is verified in practice. The program requires a visual inspection of the thermal envelope prior to drywall installation. This inspection uses criteria derived from energy code requirements for air barriers and insulation.

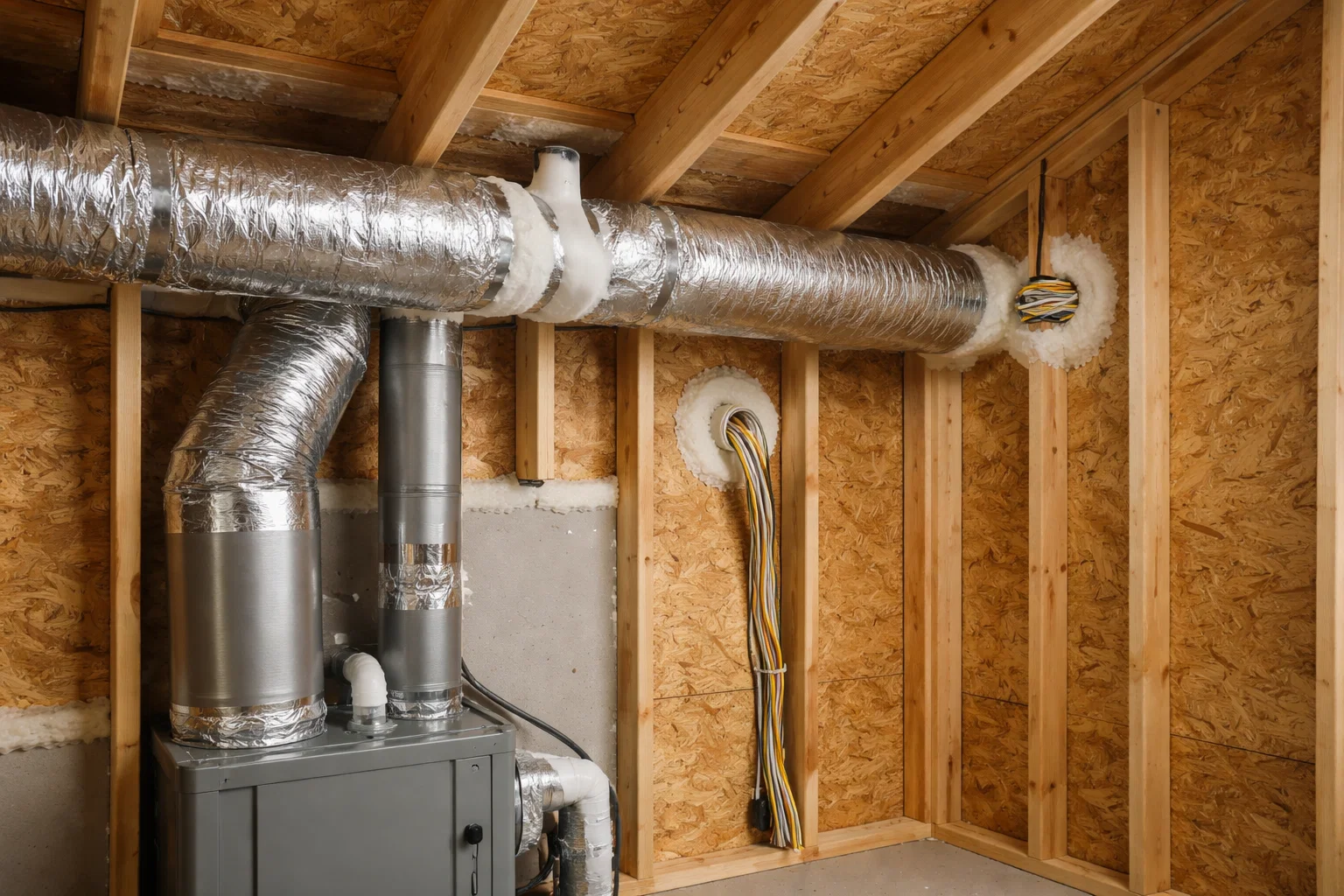

Conducting this inspection before drywall is critical because envelope components are accessible at that stage. Once finishes are installed, inspection of insulation and air barriers is no longer possible without removal. After construction, the program requires diagnostic testing. A blower door test measures air leakage across the building envelope. Duct leakage testing is required when heating and cooling ducts are present.

These tests quantify performance characteristics and highlight invisible energy features.

Mechanical Ventilation as a Required System

Installation of whole-house mechanical ventilation systems usually have to meet established standards. These systems are designed to provide controlled air movement within the home. Ventilation systems are verified through testing rather than appearance. Their components may include fans, ducts, and controls that are partially visible, but their operation and effectiveness are confirmed through measurement. Ventilation requirements reflect the relationship between airtightness and indoor air management.

As envelope tightness increases, controlled ventilation becomes a required component of the overall system.

The Role of Certified Verification

Certified HERS raters must be involved in verification. These professionals submit modeling files, inspection documentation, and test results to demonstrate compliance. The reliance on third-party verification reflects the fact that envelope performance cannot be confirmed through casual observation.

Documentation serves as the permanent record of how the concealed invisible energy features were designed, installed, and tested. Without documentation, there is no visual method to confirm the presence, continuity, or performance of envelope components once the home is complete.

Because envelope components are concealed invisible energy features, documentation becomes the only evidence of their existence and configuration. Inspection reports, test results, and program submissions establish what cannot be observed. Connecticut’s program requirements illustrate this reliance on documentation.

Compliance is demonstrated through submitted files, certifications, and verified test outcomes rather than visual review. This approach reflects the broader building science principle that performance is established through design, installation, and verification. Not appearance.

Conclusion

Residential performance as the outcome of invisible energy features including concealed systems, continuous control layers, and verified installation practices. The elements that separate the indoor environment from the outdoors, insulation, air barriers, moisture control layers, ventilation systems, and their continuity across assemblies, are intentionally hidden within the structure. They are inspected before finishes are installed and tested after construction because they cannot be evaluated visually.

These features do not appear in photographs.

They are defined by standards, assembled during construction, and confirmed through verification.

They determine how a home functions, even though they remain out of sight.

If you want to go deeper:

This article focuses on the invisible energy features that determine how a home actually performs. If your role involves listing or showing homes, our short course Low-Cost Sustainability Upgrades That Improve Listing Appeal covers how visible, affordable sustainability improvements are typically discussed in Connecticut, providing practical language agents can use without overpromising performance or savings.

- To see how these hidden elements interact with a home’s envelope, read our guide on why insulation and air sealing matter more than any single upgrade.

- If you want to understand how one core system moves heat through the home, explore Heat Pumps in Connecticut: What Buyers Really Need to Understand.

- For a look at how invisible home features are recognized during valuation, see how appraisers evaluate energy features in Connecticut.